Aikaterini Charalampopoulou 20-24 January 2020

In January 2020, I had the chance to do a one-week internship at the Gustavianum collections – an internship that was part of The Master’s Programme in Digital Humanities at Uppsala University. Time was short, but we were assigned to a series of different tasks so that to get the most out of our stay there. The collection we mainly worked with was the Valsgärde boats. Valsgärde is an area, around 3km north of Gamla Uppsala, along Fyrisön. The site was found in the 1920s and many archeological excavations were conducted in the decades that followed. The Valsgärde findings consist of 15 ship graves, dating from the 6th century and the Vendel Age to the 10th century and the Vikings times

Being engaged in this particular collection was of great personal importance to me. Valsgärde was the very first place in Uppsala I tried to visit, only a couple of days after my arrival in Sweden some years ago. I got to know about it in an old French tourist guide from the 1980’s — the famous Guide Bleu — and I immediately decided to visit it. I was never sure if I actually reached the correct location, until I showed my pictures to John Worley who confirmed that it had been the correct site.

John Worley is a curator for the Scandinavian Archaeological collection at Gustavianum and was responsible for our internship and the planning of our daily tasks. He is in many ways responsible for making it possible for us to delve into the collection despite the time limitations. This was accomplished by working with the Valsgärde boats in three ways: the actual objects, their documentation in the database and their photographic documentation. Those three approaches gave as a chance to work with the collection on different scales and from different perspectives, and at the same time to acquire a general knowledge about how life at the curation unit of the museum is.

Valsgärde boats were around 10m long each and the archaeological findings consists of valuable objects contained in the boats, as well as animals and human relics. As wood has mostly disintegrated, what has remained from the boats are their rivets. Each boat was put together with the help of more than a thousand iron rivets that archaeologists have documented by registering their coordinates, size and condition. Those rivets we had the opportunity to work closely with, freeing them from old metal labels that unfortunately have contributed to their erosion and providing them with new acid free slots. For the larger or more impressive findings of the Valsgärde boats we created customized cases by polyethylene foam, so that objects can be easily and safely kept and transferred.

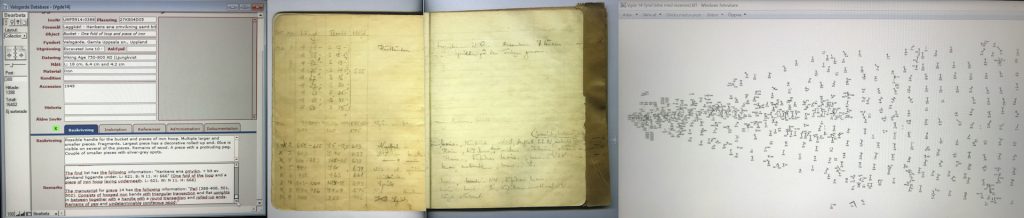

The documentation in a FileMaker Pro database consisted of consulting simultaneously various sources: the diary (Grävdagbok) that was handwritten at the site the time of the excavation, the list of findings (fyndlista) which was a typed document mostly drawing on the diary, and various maps, both small and large scale. The aim of this task was to cross-check and supplement the available data, plus to translate it from Swedish to English so that the collection eventually reaches a wider audience beyond the language barrier.

Work at the photographic lab included taking digital pictures of items in the collection. The photographic process started with the gentle placement and support of the object, and continued with selection of the correct exposure and shutter speed in order to take photographs which need as little manipulation as possible. We also familiarized ourselves with the camera’s software and Photoshop tools in order to be able to bring forward details that are not easily visible with the naked eye. Photographs taken would then be inserted to the item’s entry in the database.

Last but not least, I was given the chance and I was encouraged to follow my own research interests and gather material both for my upcoming master’s thesis and other assignments currently running on the Master’s program. In my experience, it is as much useful to enter the Gustavianum collections as open and receptive as possible, absorbing all the knowledge that is generously offered, as to have particular research questions in mind that can work as guide in the multiple and labyrinthine paths of the Gustavianum collections. In conclusion, my experience in the museum both satisfied my curiosity regarding the “backstage” of a museum i.e. its curation units, and it supported my confidence towards how I can participate and contribute in different curatorial tasks. It was an internship harmoniously related to the Master’s curriculum and I would surely repeat it if given the opportunity.