This is a guest blog post by programme director Olle Sköld that was written at the beginning of the summer of 2020 .

The academic year is at an end and it is time for some well-earned time off for both students and faculty at the DH master’s program at Uppsala University. The past two semesters have been packed with exciting courses, discussions, workshops, and for the majority of the class a second year of program studies awaits after the summer holidays. Some of the students however chose to go for a 60-credit master’s degree and have concluded the semester and their time at the Department of ALM by executing a series of impressive thesis projects that I would be amiss if I didn’t showcase here (with the authors’ permissions of course).

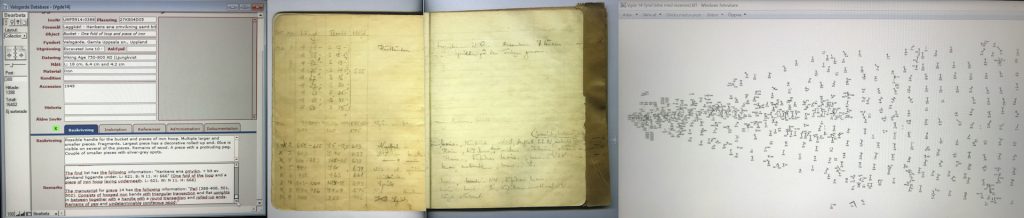

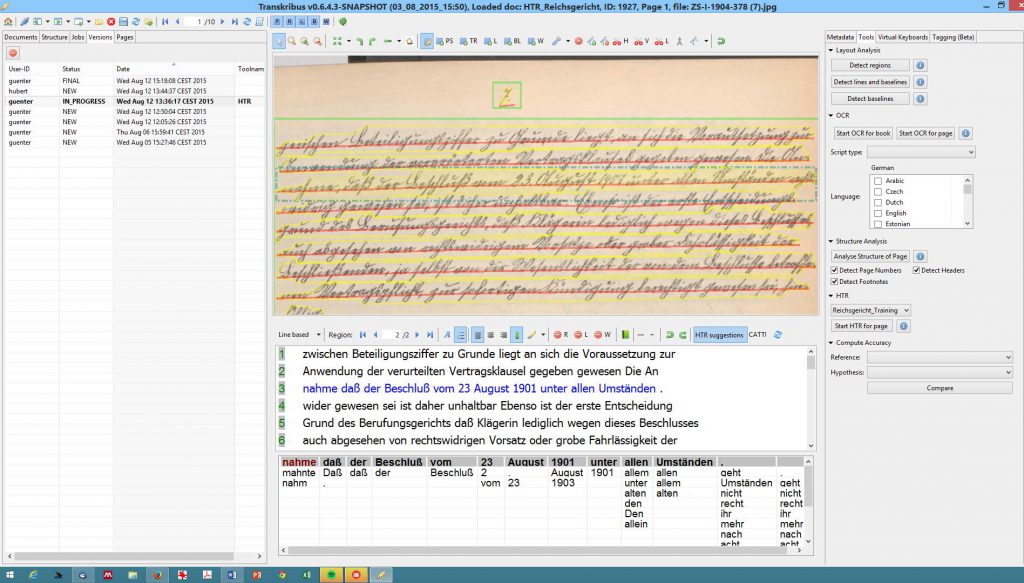

Nikolina Milioni directs attention towards a matter that is front-of-mind for libraries, archives, and scholars all around the world: handwritten text recognition (HTR). In her thesis, Nikolina evaluates and discusses the applicability and usefulness of Transkribus — a freely accessible HTR application. Nikolina describes the thesis in the following way:

Digital libraries and archives are major portals to rich sources of information. They undertake large-scale digitization to enhance their digital collections and offer users valuable text data. When it comes to handwritten documents, usually these are only provided as digitized images and not accompanied by their transcriptions. Text in non-machine-readable format restricts contemporary scholars to conduct research, especially by employing digital humanities approaches, such as distant reading and data mining. The purpose of this thesis is to evaluate Transkribus platform as a linguistic tool mainly developed for producing automatic transcriptions of handwritten documents. The results are correlated with the findings of a questionnaire distributed to libraries and archives across Europe to expand our knowledge on the policy they follow regarding manuscripts and transcription provision. A model for a specific writing style in Latin language is trained and the accuracy on various Latin handwritten pages is tested. Finally, the tool’s validation is discussed, as well as to what extent it meets the general needs of the cultural heritage institutions and of humanities scholars

Nikolina’s thesis is titled “Automatic Transcription of Historical Documents: Transkribus as a Tool for Libraries, Archives and Scholars” and a full-text copy can be downloaded from DiVA.

Ylva Arwidson sets out to shed further light on nature of communication practices and public relations the in the present-day digital arena. This done by the way of an interview-based case study of how digital coordinators enact and understand public-relations work in the Swedish cultural heritage sector. Ylva summaries her thesis in the following way:

This research is about Swedish cultural institutions’ digital public relations work, with the purpose of investigating what the digital coordinators at the institutions consider to be essential skills in their work and how they define and implement effective and successful communication online. Communicating about culture and cultural heritage is essential and a key priority in order to ensure that the public is educated about the past as well as the present. Through analysing data from interviews conducted with professionals working within communications at Swedish cultural institutions, the study investigates what the main difficulties, similarities and dissimilarities are in digital public relations today and why.

The results show that the professionals’ main areas of difficulty lay within conciseness and correctness, these could be attributed to lesser constraints in the digital setting, inattention, the faster pace of working online as well as a higher tolerance for errors. The interviewees showed a dependence on adding links to their digital content, expressing different opinions regarding what purpose linking serves. There is a common trend within the professionals’ work in favour of democratisation of the dynamics between the institution and the public – two-way communication through adapted and personalised dialogue (community management) and valorisation of feedback. The study provides first-hand insight into the strengths and weaknesses of digital public relations actors working within Swedish cultural institutions.

Ylva’s thesis is titled “Digital Public Relations in the Swedish Cultural Sector: A Study of Effective PR and Two-Way Communication” and a full-text copy can be downloaded from DiVA.

Nadim Herbert ventures to create new knowledge about the mechanisms underpinning the phenomenon called ‘woke-washing’ in his thesis. Woke-washing takes place when brands and corporations makes use of (socially, culturally, politically) progressive values in service of marketing or PR campaigns. The empirical basis of Nadim’s study is an analysis of Twitter data consisting of both posts and thousands of user responses. Here’s Nadim’s rendering of the thesis:

This study examines two marketing campaigns on the social media platform Twitter by the brand Nike, with the campaigns involving American football player Colin Kaepernick and tennis player Serena Williams respectively. The study specifically explores how Nike utilizes socially and politically progressive values in these marketing campaigns and how users then respond to it on Twitter, with the source material consisting of four Twitter-posts, two by Nike and one each by the two athletes involved, as well as the replies by other Twitter-users to those posts. The replies to these four Twitter-posts were then sorted into reply types for each post, in other words categorized according to the sentiments and attitudes in the replies that were most prominently and frequently expressed. A grounded theory approach was used thereafter in order to apply relevant theoretical perspectives to the reply types and original posts, through which the source material was split into several analytical themes. The theoretical perspectives used in the analysis were Rosalind Gill’s postfeminist sensibility, Ron Von Burg and Paul E. Johnson’s writings on nostalgia as a critical perspective, Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe’s floating signifier concept, Eduardo Bonilla-Silva’s racial grammar theory, Susan Cahn’s writings on female athlete stereotypes, and Lauren Copeland’s writings on postmaterialism.

The analysis showed that Nike utilized socially progressive causes such as racial and gender equality in an individualistic way by conveying them through the identities of Williams and Kaepernick in their Twitter-posts. It also showed that the replies to the marketing in turn also focused on the identities of the athletes, with repliers either declaring their approval or disapproval of Nike and their marketing campaigns based on whether they were ethically and ideologically aligned with the progressive causes and values that the athletes were proxies for in their respective marketing campaigns. Ultimately, this study revealed an individualization of political expression on social media, both when a corporation like Nike uses it to improve their brand image and in how individuals engage with political and social issues.

Nadim’s thesis is titled “‘Woke-Washing’ a Brand: An Analysis of Socially Progressive Marketing by Nike on Twitter and the User Response to it” and a full-text copy can be downloaded from DiVA.

The topics explored in these theses really illustrates the breadth and relevance(s) of the DH field for both digital professionals and SSH research. Congratulations to Nikolina, Ylva, and Nadim for their excellent efforts on the DH programme! Now I’ll transition from spring semester to summer holidays happy with the knowledge that many more thought-provoking and interesting thesis projects will be carried out under the auspices of the Master’s Programme in Digital Humanities in the semesters to come.