This is a guest post by Daniel Löwenborg, researcher and senior lecturer at the Department of Archaeology and Ancient history.

Digital Archaeology

Archaeology has a long tradition of working interdisciplinary and have been using digital technology extensively, especially since GIS (geographical information systems) became more widely available in the 1990s. Since archaeological information is inherently spatial, the use of GIS has proven to be very useful and is now well integrated in the discipline and in several of the research projects running at the department of archaeology and ancient history in Uppsala. There are also a number of research infrastructure project running, with the focus on digitizing information and making it available. Examples include the project Common Ground in collaboration the Swedish institutes in Athens, Rome and Istanbul, that is digitizing material produced in excavations in the Mediterranean area. The project Urdar, in collaboration with the Swedish National Heritage Board, is making digitally born data from archaeological excavation in contract (rescue) archaeology available for research, and will also undertake digitalisation of analogue documentation. The project “Re-imag(in)ing the Scandinavian joint expedition”, is a pilot project that will do initial digitalisation of a collection of archival records from the Scandinavian Joint Expedition to Sudanese Nubia (SJE) (1961–64). The project “Mapping Africa’s Endangered Heritage” coordinated by the University of Cambridge is an ambitious infrastructure project involving several international partners, where Uppsala will be responsible for creating a database of archaeological sites in Zimbabwe.

A common thought behind these projects, representing the subdisciplines at the department (classical archaeology, Scandinavian archaeology, Egyptology and African and comparative archaeology) is the greater benefit that will come when researchers have access to digital information, both to facilitate searches and queries, but also to enable data driven research using methods from computer science.

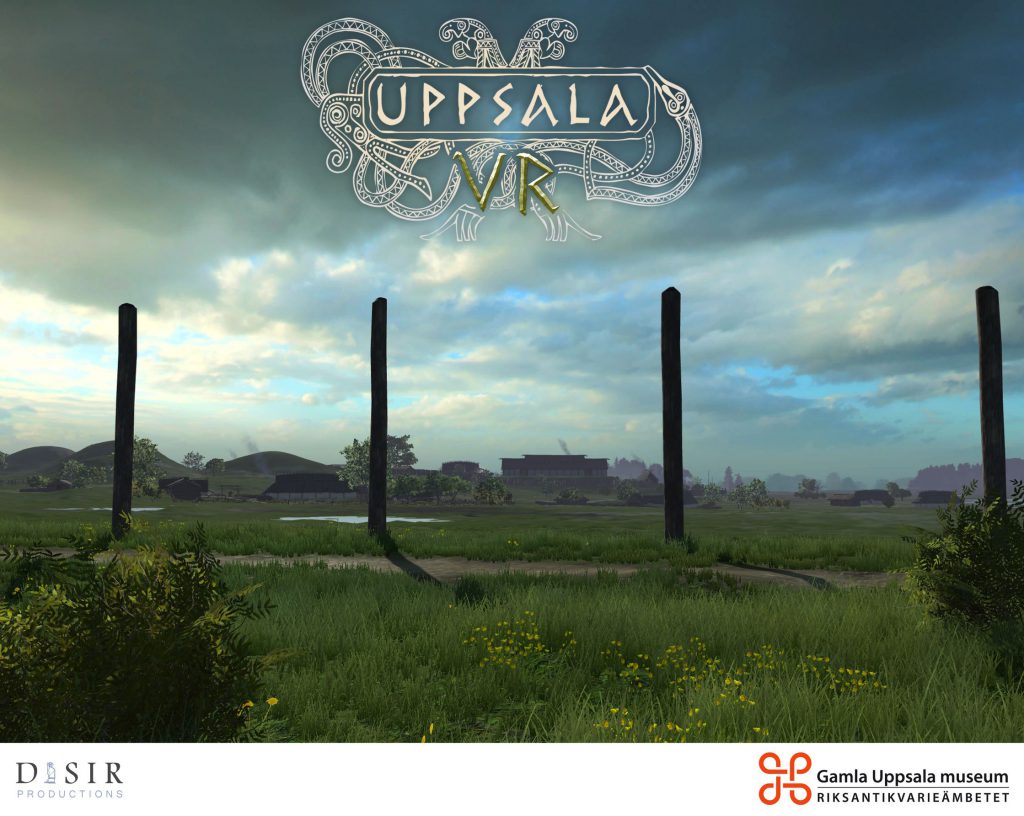

Another aspect of digital archaeology comes with the possibilities of visualisation and presentations using 3D technology. A long-term research project at Gamla Uppsala has produced advanced digital environments that can be used both as a mobile app, that allows visitors to Gamla Uppsala to walk around at the site and see an interpretation of what the place might have looked like in the 7th century AD. This has also been developed to a digital time machine using virtual reality, that can be experienced at the museum.

A project starting in 2020 is a combined research project in history, coordinated by Rosemarie Fiebranz, where the aim is to do a digital historical reconstructions of the village Ekeby, near Vänge outside Uppsala. This is also the case study we are using for the Digital Humanities master course module on Visual Analysis, where the students get a chance to work with 3D modelling of building from Ekeby and create animations of the historic environment in GIS. This is coordinated by Daniel Löwenborg, who also teaches the master course on “GIS for the Humanities and Social Sciences”, that is one of the optional course for the students on the Master program. That course runs in the autumn and introduces more of the potential of working with GIS for digital humanities.

At the Department of ALM, we try to encourage our students to travel to conferences, workshops and meeting so that they also can get important academic- or work connections for their future career. Every semester a number of students get grants from the department for going away. We have sent students to UK, Estonia, Argentina, Finland, Germany…. Many of them have shared their experiences in the department journal,

At the Department of ALM, we try to encourage our students to travel to conferences, workshops and meeting so that they also can get important academic- or work connections for their future career. Every semester a number of students get grants from the department for going away. We have sent students to UK, Estonia, Argentina, Finland, Germany…. Many of them have shared their experiences in the department journal,